- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- Mochica Agriculture: The Foods and the Farmers

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

International academic cooperation between the Wiese Foundation and Universidad Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul ...

Clothing at El Brujo: footwear ...

To receive new news.

Por: José Ismael Alva Ch.

José Ismael Alva Ch.

Agriculture is one of the most important economic activities in the history of humanity, as its development constituted a revolution in the supply of foods. This, however, was possible thanks to the process of domestication of plants, which, in the case of the Andes, dates back 11 thousand years.

The ancient Peruvians knew very well how to take advantage of the resources of the environment. Thus, they learned to recognize which specimens grew best in each of the ecological floors of the Andes Mountain Range, and they also created agricultural calendars that allowed them to organize the sowing and harvesting times.

Taking as a background the experiences of ancient societies, when the Mochica developed in the North Coast of Peru (between 100 and 800 AD), they already had access to a wide diversity of plants and agricultural knowledge. For example, as they came after the Gallinazo epoch (Gagnon, 2008; Lambert, 2012), the Mochica were able to enjoy the expansion of the valleys through the construction of irrigation canals between the years 200 BC and 100 AD.

What food plants did the Mochica handle?

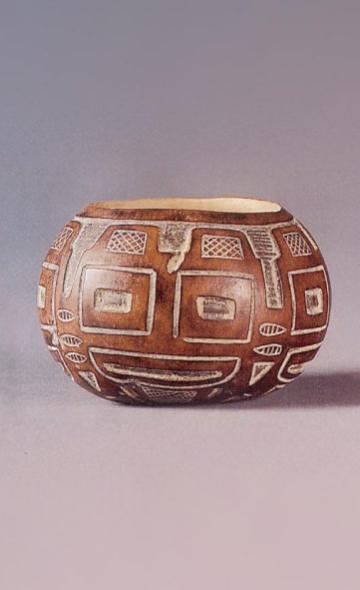

The studies carried out in the Mochica settlements have made it possible to learn which were the plants that they consumed. Thus, we know that in urban areas such as Huaca Cao Viejo (Chicama Valley) and Huaca de la Luna (Moche Valley), they cultivated cereals such as corn, fruits such as cherimoya, soursop, friar’s plum, South American apricot, chili, cucurbita squash, gourd, lúcuma and guava; legumes such as peanuts, pacae (Inga brachyptera), gentiles lima bean, lima bean, beans and carob, and tubers such as potatoes, sweet potatoes, yucca and achira. It is worth mentioning that, among the latter, the potato is the specimen that can be cultivated on various ecological floors, although it grows in better conditions between 2000 and 4000 meters above sea level.

Regarding the way in which these products were consumed, we know from the research conducted that, in the case of legumes, some were eaten cooked together with other foods; others were eaten toasted or fresh, as in the case of pacae. Regarding corn, it was not only present in foods, but also in drinks such as the corn-based chicha drink. In relation to the latter, there are vestiges of a chicha preparation and storage area in the Las Tinajas sector of the El Brujo Archaeological Complex, as well as in the urban area of Huaca de La Luna. According to Gummerman (2010), chicha was served in communal festivities, as well as in commemorative ceremonies.

What do we know about the farmers of the Moche epoch?

In ancient Peru, the tasks related to sowing, cultivating and harvesting were distributed among the members of the family unit, so it is not appropriate to consider that only men were engaged in agricultural work. Also, the participation of the boys and girls ensured that they learned the activities of the field from a very young age.

Excavations at the Huaca de La Luna have revealed that the population dedicated to agriculture did not live in urban areas, where the Moche elite, through the temples, dominated the destinies of social life. These families lived in villages distributed near the cultivation areas, and, probably, the internal organization of the settlement (government and labor management) was carried out through kinship ties. Unfortunately, the structural precariousness of these homes, and their location close to the sowing fields, makes it almost impossible for archaeologists to find and study them.

Examples of the villages mentioned above are the rural settlements of Santa Rosa de Quirihuac (Early Moche phase) and Ciudad de Dios (Late Moche phase) in the middle Moche valley, 12 km east of Huaca de la Luna. These differ because in the first settlement there was limited access to agricultural products, among which the consumption of beans, lima beans and gentiles lima beans were prominent; while in the second settlement, the existence of social hierarchies within the village became increasingly evident, with the emergence of a rural elite that supervised food production (Gummerman and Briceño, 2003, p. 231-232). This elite also offered large communal banquets where a relevant portion of agricultural products, camelid meat and chicha were consumed as compensation for carrying out the tasks of the field in favor of the Mochica State (Gummerman and Briceño, 2003, p. 239).

In summary

The diversity of plants accessed by the Mochica was the result of the domestication and conditioning processes of new cultivation areas carried out by their predecessors in previous centuries.

The agricultural infrastructure and the efforts of the Mochica farmers were the basis for the supply of food that, to a large extent, sustained life in urban areas, where the priestly class and the most outstanding artisans of society resided. Although large communal banquets have been documented in villages and urban areas, these occurred exceptionally and not as part of the daily life of the populations. More detailed examinations of new contexts related to the daily life of the Moche should reveal to us whether, indeed, the diversity of foods was distributed without major social distinction among the Mochica populations.

Bibliography

• Gagnon, C. (2008). Bioarcheology Investigations of Pre-State Life at Cerro Oreja. L.J. Castillo, H. Bernier, G. Lockard, and J. Rucabado (Eds.), Mochica Archeology. New Approaches (pp. 173-185). Lima: Fondo Editorial de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú and Institut Français d'Études Andines

• Gummerman, G. (1998). Paleobotanical Research in the "El Brujo" Complex. R. Franco, C. Galvez and S. Vásquez (Eds.), El Brujo Complex Archaeological Program. Final report. Season 1998 (pp. 81-84). Wiese Foundation.

• Gummerman, G. (2010). Big Hearth and Big Pots. Moche Feasting on the North Coast of Peru. E. Klarich (Ed.), Inside Ancient Kitchens. New Directions in The Study Daily Meals and Feasts (pp. 111-131). University Press of Colorado.

• Gummerman, G. and Briceño, J. (2003). Santa Rosa - Quirihuac and Ciudad de Dios: rural settlements in the middle part of the Moche valley. S. Uceda and E. Mujica (Eds.), Moche: towards the end of the millennium, Volume I (pp. 217-243). Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Universidad del Perú

• Lambert, P., Gagnon, C., Billman, B., Katzenberg, A., Carcelén, J. and Tykot, R. (2012). Bone Chemistry at Cerro Oreja: A stable isotope perspective on the development of a regional economy in the Moche valley, Peru during the Early Intermediate Period. Latin American Antiquity, 23 (2), 144–166.

• León, E. (2013). 14,000 years of food in Peru. Lima: Fondo Editorial Universidad de San Martín de Porres.

• Mujica, E. (Ed.) (2007). El Brujo. Huaca Cao, Moche Ceremonial Center in the Chicama Valley. Lima: Wiese Foundation.

• Vásquez, V., Franco, R. and Rosales, T. (2014). Ancient starches from the dental calculus of a Mochica burial at Huaca Cao Viejo, El Brujo archaeological complex, north coast of Peru. Archaeobians, 8 (1), 6-16.

• Vásquez, V. and Rosales, T. (2004). Archaeozoology and Archeobotany of Huaca de la Luna, 1998-1999. S. Uceda, E. Mujica and R. Morales (Eds.), Research in the Huaca de la Luna 1998-1999 (pp.337-366). Trujillo: Universidad Nacional de Trujillo.

• Vásquez, V. and Rosales, T. (2006). Analysis of Organic Remains (Zoological and Botanical) of CA-35 and CA-17, Moche Urban Zone - Huaca de la Luna. S. Uceda and R. Morales (Eds.), Huaca de la Luna Archaeological Project. Technical Report 2005 (pp. 275-302). Trujillo: Universidad Nacional de Trujillo.

Researchers , outstanding news